Dr. HyeRan Choo and the non-surgical Orthodontic Airway Plate treatment at Stanford

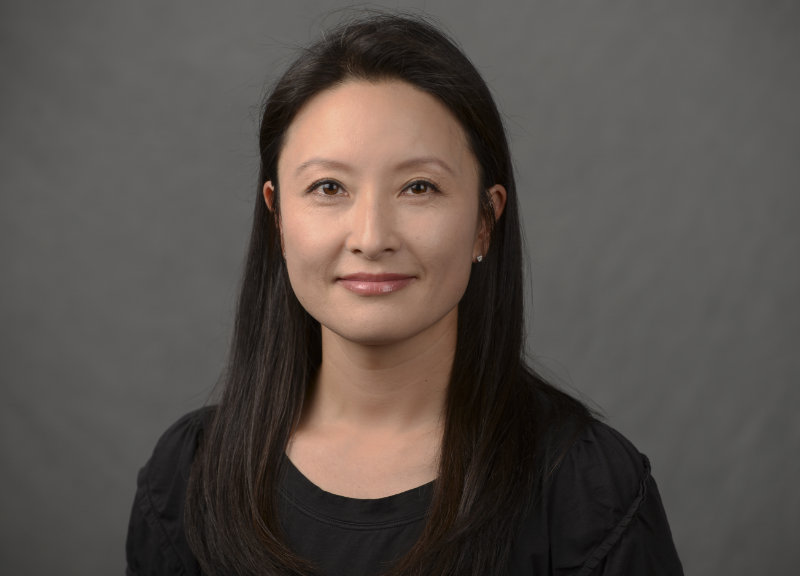

Dr. HyeRan Choo, Clinical Assistant Professor of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Stanford University School of Medicine, speaks with us about the breakthrough non-surgical treatment she and her team offer to Pierre Robin Sequence babies at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford in Palo Alto, California. Dr. HyeRan Choo is Director of Neonatal and Pediatric Craniofacial Airway Orthodontics and Dental Sleep Medicine in the Department of Surgery, Director of Neonatal and Pediatric Craniofacial Airway Orthodontic Fellowship, and a Faculty Fellow of the Stanford Byers Center for Biodesign at Stanford University.

HyeRan Choo, DDS, DMD, MS; Neonatal and Pediatric Craniofacial Airway Orthodontics and Dental Sleep Medicine; Stanford University / Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford

Q: Dr. Choo, thank you very much for taking the time to speak with us about your work. Before talking about Pierre Robin Sequence – let’s call it RS – can you begin by telling us about your professional background? Where did you study dentistry and orthodontics and what additional specialized training did you receive? Also, where do you practice today?

A: Thank you Philippe for interviewing me on the topic of neonatal RS. I am a Korean American, born and grew up in South Korea. My professional background starts from completing dental surgery training at Seoul National University in Korea in 2002. I also completed dental medicine training at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia in the U.S. in 2004. I became an orthodontist in 2007 by training at the University of Alabama at Birmingham through three years of orthodontic residency and Masters in Science program. I went on to completing the craniofacial fellowship in 2008 at the National Institutes of Health / National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research in Bethesda. Immediately following the fellowship, I was recruited as a full-time faculty member at the Craniofacial Center of the University of Pennsylvania / The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). I moved to San Francisco Bay area in 2012 for family reasons and stayed relatively dormant to raise children of my own for several years. I joined the faculty of Stanford University School of Medicine / Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford in Palo Alto in the U.S. in 2016 and this is currently where I am practicing neonatal and pediatric craniofacial and airway orthodontics and dental sleep medicine.

Q: When did you first become interested in RS – and out of all the conditions out there, why RS?

A: I first became interested in RS when I saw several RS children at CHOP who had jaw distraction surgeries during the first year of their lives. Parents were bringing their children to my clinic when they were six to seven years or older with concerns such as “lower molars not coming out”, “can’t open the mouth”, “we are thinking about another jaw distraction surgery soon because the jaw is still too small and we have sleep apnea”, etc. As a rookie craniofacial orthodontist, I knew jaw distraction surgery for babies was necessary for them to breathe. I just felt bad that they had to go through hardware installation and removal surgeries through the bone and skin, which seemed to disturb the growth center and growth sites of the lower jaw bone and primary and/or permanent tooth bud formation.

In general, I like building an initial foundation for success that has long lasting positive effects in life. As a neonatal craniofacial airway orthodontist, I see myself in a position where I can situate RS babies to set off to a good start to their lives in a way that minimizes surgical, orthodontic, and dental interventional needs in the coming years despite their congenital craniofacial challenges.

Neonatal RS is one of the most challenging congenital conditions to manage for medical, surgical, and orthodontic providers due to babies’ functional difficulties such as breathing and feeding and anatomical disadvantages such as small jaw and cleft palate. The fact that I can help them potentially avoid surgery early in their lives with a nonsurgical treatment and that they can go on their lives like any other children without congenital oral facial disparities is exciting and very rewarding.

Q: I’d like to discuss with you some of the RS research you and your colleagues have carried out at Stanford. Let’s begin with the article titled “A Systematic Review of Mandibular Distraction Osteogenesis Versus Orthodontic Airway Plate for Airway Obstruction Treatment in Pierre Robin Sequence”. In this article your team compared two different RS treatments: (1) a surgical approach, mandibular distraction osteogenesis (MDO); and (2) a non-surgical approach, the orthodontic airway plate (OAP). In order to compare these two different treatments, your team actually went through and read a whole bunch of previously published studies, then analyzed the data. The data indicated that the OAP treatment was as effective as MDO, for relieving the RS baby’s upper airway obstruction. Is this what you were expecting to see?

A: As we started implementing the orthodontic airway plate (OAP) treatment for our RS babies more frequently at our institution, my colleagues who were unfamiliar with the OAP treatment at that time were curious to know what was known in the literature regarding the OAP’s effectiveness relative to MDO surgery. As we mentioned in the discussion of the article, direct comparisons between MDO and OAP have inherent limitations due to the lack of standardized subjective and objective metrics for pre-treatment assessment and post-treatment outcome measures, sample size difference, and potential publication bias. With these limitations in mind, we became optimistic after the systematic review that the current literature supports that the OAP treatment can be a safe and effective nonsurgical treatment option for neonatal RS management. Much more research is to be done to fully understand each treatment modality in a standardized manner though.

Q: When surgeons first started performing MDO on RS babies it was considered a big step forward, because it reduced the need for a tracheostomy. The research which you and your colleagues carried out confirmed this; according to the data, 90% of RS babies who underwent MDO were able to avoid a tracheostomy. However, the data also showed that the non-surgical approach – the OAP – was just as effective at helping RS babies to avoid tracheostomy: 96% of the RS babies who were treated with the OAP were able to avoid tracheostomy. Is this correct?

A: Yes, that is correct. Tracheostomy is a surgery that lets a baby breathe through the lower airway only (bronchi and trachea) bypassing the upper airway (larynx, pharynx, and nasal cavity) and leaves the upper airway still obstructed. Even though the indication criteria and the timing for tracheostomy might vary from center to center and the sample size of the OAP-managed groups was smaller approximately threefold than that of MDO-managed groups, the results show that OAP can be as effective as MDO in terms of avoiding tracheostomy and decannulating the previously done tracheostomy.

Q: Previously, “avoidance of tracheostomy” was considered a basic metric of success when it came to RS care. I think your “Systematic Review” paper forced us to revisit the definition of what “success” is, and approach it in a more ambitious way. With the OAP treatment you’re no longer just talking about avoiding tracheostomy. You’re talking about avoiding tracheostomy, but you’re also talking about avoiding MDO surgery, and avoiding tongue-lip adhesion (TLA) surgery too. Basically your goal is to resolve the RS baby’s upper airway obstruction without any of those surgical procedures, right?

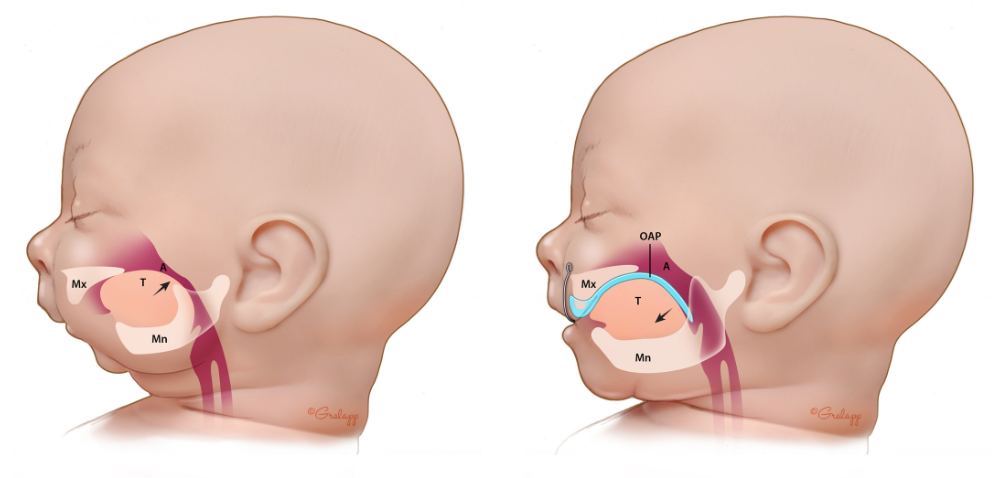

A: Yes, the goal of the OAP treatment is avoiding MDO, TLA, and tracheostomy when the baby’s breathing difficulty is resulted primarily from the mechanical obstruction by the tongue. To make the OAP treatment work, the very first step is to make the OAP fit comfortably and also adjust it for the baby’s needs. OAP opens the blocked upper airway immediately following the device delivery to the RS baby’s mouth. By the time we consider discontinuing the OAP treatment in the coming months, the baby’s jaw would have grown significantly (mandibular catch-up growth) and the tongue would have been trained to stay forward with the grown lower jaw, rather than habitually sitting back blocking the upper airway. The goal of MDO, TLA, and tracheostomy is letting the RS baby breathe well at all times. So, if the OAP can let the baby breathe well at all times, there will be no reason to get the surgery.

Q: Let’s back up a bit and talk about orthodontic plates. Orthodontic plates are not a new treatment, I mean based on my understanding, basic orthodontic plates, for instance the conventional, flat palatal plate, has been in use for 50 years or longer. What was the purpose of some of those early orthodontic plates?

A: Yes. Neonatal orthodontic treatment using removable oral plates was first introduced in 1950 by Kerr McNeil, a dentist in Glasgow Scotland, to alleviate orofacial cleft disfigurement and to enable bottle feeding for babies born with cleft lip and/or palate. When the muscles of the soft palate are clefted (separated), negative pressure that sucks milk out of the bottle or mom’s breast still cannot be restored even though the oral cleft is obturated using a removable oral plate. However, babies can express milk more effectively from the bottle by compressing the nipple against a hard acrylic plate. To date, this treatment concept is utilized with various modifications in the field of neonatal cleft management.

For the airway management, it was William Pielou, a dentist in Northern Ireland, that applied removable oral plates for RS babies for the first time in 1967. He designed an oral plate with a vertical extension to the throat that kept the tongue from prolapsing. In addition, he was one of the first doctors who emphasized the importance of the bottle-feeding by the baby’s own tongue and jaw movements instead of spoon feeding or tube feeding, which was the gold standard at that time, in treating breathing difficulty of RS babies.

Q: In another article you and your colleagues published in this series: “Nonsurgical Orthodontic Airway Plate Treatment for Newborns With Robin Sequence”, you described a more advanced version of the airway plate. This advanced version was developed by a German orthodontist, Dr. Margit Bacher, at the Tübingen University Hospital. It’s known as the “Tübingen Palatal Plate”, or TPP. Can you tell us about this?

A: Yes, my understanding is that Margit Bacher, an orthodontist in Tübingen in Germany, had the opportunity to work with William Pielou. Together, they advanced the clinical application of airway plates to the next level. Dr. Bacher succeeded in visualizing the placement of the vertical extension inside the baby’s mouth by collaborating with neonatologists in Tübingen who performed fiberoptic endoscopy while the baby was crying, breathing, and swallowing. Their airway plate’s name is Tübingen Palatal Plate (TPP). A fiberoptic endoscope is like a long, thin, flexible video camera. Using this device, healthcare providers can see down the baby’s throat and determine the appropriate length, width, and angle for the vertical extension of the airway plate. Dr. Bacher has also designed several modified airway plates that have an artificial pharyngeal airway when the upper airway obstruction occurs not only by the prolapsing tongue but also by the concurrent constriction of the pharyngeal walls. The RS Center in Tübingen Germany is run by a team of world expert neonatologists, orthodontists, oral maxillofacial surgeons, and infant feeding specialists. The Center uses TPP as the first line treatment for all RS babies with tongue-based airway obstruction.

Above, Split orthodontic airway plate – Dr. Choo’s OAP design.

An illustration of how the OAP works. T: tongue, A: Airway, Mx: Maxilla (upper jawbone), Mn: Mandible (lower jawbone), OAP: Orthodontic Airway Plate. In the illustration on the left, the RS baby has no OAP; the raised position of the tongue, standing up in the back of the throat, blocks the upper airway, creating potentially life-threatening breathing and feeding difficulties. In the illustration on the right, the OAP is in place; it is represented by a cyan blue line. The cyan blue line begins at the upper alveolar ridges, where the upper front teeth will eventually grow; it continues along the upper palate and helps to cover the cleft in the palate; then it extends down, almost vertically. In the image on the right, toward the right side, we can see this downward dipping cyan blue line; it is pushing the base of the tongue toward the front of the mouth. By shifting the tongue forward, the OAP instantly liberates the throat – without surgery.

Q: I’d like to ask about the vertical extension which we see on the OAP, I mean the vertical part which pushes the tongue forward and gets it out of the way of the RS baby’s throat. Now I understand that this vertical extension is custom made, with precise measurements, based on what the clinicians see when they do the fiberoptic endoscopy (flexible video camera) exam. But how can you really know that you’ve gotten the right measurements for this particular baby? How can you be sure that your measurements are correct?

A: The vertical part of the OAP is called pharyngeal component or velar spur. The fiberoptic endoscopy exam provides visualization of the position of the velar spur relative to other pharyngeal and laryngeal anatomy during baby’s normal functions such as breathing, swallowing, crying, and mouth opening and closing to make sure the pharyngeal component does not irritate those actively moving tissues at any moment. The precise measurements of the pharyngeal component are needed during the fabrication stage of the OAP in my orthodontic laboratory and I obtain those measurements by analyzing the baby’s face CT (computerized tomography). CT capture static images of the oral, nasal, and pharyngeal structures in three dimensions. Since babies move these structures almost constantly, the dynamic relationship of the pharyngeal component of the OAP inside the throat must be confirmed using fiberoptic endoscopy.

Q: Just a practical question. You said that with the OAP treatment, the baby spends 2 to 3 weeks in the hospital. What happens next? How long does the RS baby continue wearing the plate?

A: It takes about a week or so to confirm whether the OAP treatment will work out well for the baby in the long run. Immediately following the delivery of the OAP, the baby’s breathing is expected to become stabilized and can sleep well on its back in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). During this one week of OAP trial period, a post-OAP delivery sleep test is conducted to confirm the breathing stability. By the end of this first week, the baby will have already started some degree of bottle feeding in a well-coordinated suck-swallow-breathe manner with self-pacing. The second week is usually spent for parents to learn how to handle the OAP and perform the daily cleaning routine. Once parents achieve full competency, then the baby can go home with the OAP. After hospital discharge, the baby is followed by the same team of otolaryngologists, infant feeding specialists, and neonatal airway orthodontist at the outpatient specialty clinic once a month. On average, the baby will wear the OAP for about 3-6 months. At outpatient visits, each component of the OAP (extraoral wire component, palatal component, and pharyngeal component) is adjusted to accommodate the natural growth of the upper jaw and to further stimulate the lower jaw growth. Most babies achieve full bottle feeding during the outpatient visit period.

Q: You also mentioned what sounded like a series of polysomnography/sleep study exams. Why is it so important to carry out these polysomnography/sleep study exams when treating RS babies? Why should RS parents and clinicians be so concerned with polysomnography exams and “obstructive sleep apnea”?

A: Polysomnography (PSG) data are important in assessing whether a baby’s breathing difficulty comes from mechanical obstruction somewhere in the airway (obstructive apnea, mixed apnea, or obstructive hypopnea) or from lack of desire to breathe (central apnea) and how they associate with the state of oxygen saturation and carbon dioxide ventilation. PSG data also provide sleep architecture with sleep stages and nature of arousals. If an RS baby has breathing difficulty primarily due to central apnea, none of MDO, TLA, or OAP would help baby’s breathing. However, if the cause to the breathing difficulty is related to obstruction and the flexible fiberoptic endoscopy confirms tongue-based airway obstruction, any treatment that can address the tongue-based airway obstruction will be helpful for RS babies to breathe better. Both the post-treatment sleep respiratory indices such as obstructive apnea index, mixed apnea index, obstructive hypopnea index, or combination of these indices and clinical monitoring such as weight gain trajectory and behavioral changes during bottle feeding are essential in determining resolution, improvement, or worsening of breathing condition of RS babies.

At our institution, PSG data are obtained prior to initiating the OAP treatment (if possible), 3-4 days after the baby started to wear the OAP at all times, 3 months after starting the OAP treatment, and 1 month after discontinuing the OAP treatment. The baseline PSG (prior to any intervention) is useful to confirm the nature of breathing difficulty (obstructive vs central). However, the number of events of airway obstruction represented by respiratory indices does not necessarily predict whether the OAP will be successful or not, and our knowledge in this area is still evolving. Therefore, sleep respiratory indices alone should not be used as a major criterion to decide on a specific intervention for breathing difficulty for RS babies. When treating an RS baby with an OAP at our institution, we aim to bring the combined indices of mixed apnea and obstructive apnea down to less than 4 events per hour (by PSG) or 3 events per hour (by polygraphy) 3 to 4 days after the OAP is delivered, since that is the published reference value in the literature as an acceptable OAP placement in resolving the breathing difficulty for RS babies.

Newborns sleep 16 to 18 hours a day on average. If the baby’s sleep is disturbed by obstructive breathing difficulty, the sleep gets fragmented and baby’s growth and development that occur during sleep gets interrupted. Obstructive breathing difficulty not only causes sleep fragmentation but can also result in frequent oxygen desaturation and chronic hypoxia. Low oxygen saturation (hypoxia) is a well-known risk factor against normal brain development. When breathing is not comfortable, a baby’s suck-swallow-breathe mechanism gets compromised, subsequently resulting in feeding and swallowing difficulties. Without comfortable breathing at all times, it is hard to expect a baby to thrive during one of the most critical formative years of their lives.

Q: OK, so for an RS baby, polysomnography exams are super important. I have a follow-up question about this. You’ve said that an RS baby should undergo multiple polysomnography exams, at different points in time. Can you explain why? Why is it not enough to do just one single polysomnography exam?

A: The nature of the PSG scoring system is still subject to human interpretation and somewhat vulnerable due to relatively weak interscorer reliability. However, PSG is currently the most sophisticated tool available in quantifying sleep itself and sleep respiratory conditions. Therefore, comparing the PSG data from before and after a respiratory intervention can provide insights on the effectiveness of the offered treatment. For example, when the OAP treatment is trialed for an RS baby, a baseline PSG is obtained prior to the delivery of the OAP to assess the nature of breathing difficulty of the baby. A second PSG is obtained a few days after the OAP is delivered. Any changes that occur during the second PSG, therefore, can be considered the results from the application of the OAP treatment. If some specific sleep respiratory parameters are still not within a reasonably acceptably range, then the OAP needs to be adjusted.

A few days after the OAP is adjusted, another PSG is obtained to see the effects of the adjusted OAP placement. Once it confirms that the obstructive respiratory events per hour is within reasonable range, then the baby is discharged home with the OAP. Approximately 3 months into the OAP treatment, another PSG is obtained to monitor the long-term progress of sleep and sleep respiratory conditions with the use of the OAP. Another PSG is obtained approximately a month after the OAP is no longer in use.

Q: As an international RS patient advocacy group, we are in touch with a lot of RS parents. Sometimes doctors tell us RS parents, “don’t worry, the breathing problems will naturally disappear by the time your baby is one year old”. What do you think of this “wait and see” approach?

A: Watchful monitoring might be applicable only when a baby shows close to normal range of PSG results and establishes a comfortable bottle feeding routine despite a small jaw. If a baby has retrognathia/micrognathia (small jaw), glossoptosis (prolapsing tongue blocking the throat), obstructive respiratory events (breathing difficulty), feeding difficulty due to discordant breathing while feeding, and/or parents have to constantly change the baby’s sleep position or wake up the baby to breathe, watchful monitoring might not be the best approach both for the baby and the parents simply because it’s too stressful for parents to be on the lookout at all time. I think it is very important to establish comfortable breathing and subsequent self-paced suck-swallow-breathe mechanism for bottle feeding as soon as possible to help the baby to thrive and to improve the quality of life for the entire family.

Q: Let’s go back to the OAP itself. In 2019 – if I’m correct about the dates – you and your colleagues at Stanford officially adopted Germany’s Tübingen Palatal Plate / TPP treatment. This means that you, Dr. HyeRan Choo, were the first doctor anywhere in the United States of America to use this highly specialized orthodontic technique for treating RS babies. What did your colleagues at Stanford think, I mean how did they react, when you first expressed your interest in pursuing this non-surgical, orthodontic technique?

A: Actually, I did not know about TPP when I first treated my very first RS baby at Stanford in 2019. And the baby was not even Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford’s baby. It was a baby girl born at our neighbor hospital and their craniofacial team was managing the baby with the plan for jaw distraction surgery. Mom somehow found me as an expert who treats neonates using various removable oral devices and she transferred her baby daughter’s care to me. Her hope was to avoid the jaw surgery. I told mom that the design I use for those removable oral devices has a component that helps babies breathe better and help babies to train with proper tongue positions and I think that might be helpful for her baby. We initiated the treatment and mom noticed that her baby girl was getting better with breathing and feeding. Their managing team at the neighbor hospital wanted to run another sleep test a few weeks after we initiated the treatment. Their sleep medicine doctor and the plastic surgeon were quite surprised with the sleep test results. They were ok to postpone the jaw surgery and wanted to re-test her sleep in about three months. She wore the device during that time.

Her 3 month follow up sleep test results showed further significant improvement and all parties involved in her care agreed that she did not need the jaw surgery. We were all very excited with the results. So, I thought I should publish this treatment outcome. I started to look further into what’s already been published. And that’s when I discovered that this treatment concept was applied on 10 RS babies and published over 50 years ago (Pielou, 1967) and they all avoided tracheostomy which was the gold standard of care for neonatal RS management at that time. And I also found out that Tübingen University Hospital in Germany has been using this treatment as the first line treatment for all their RS babies for close to 20 years. I learned that in Tübingen, the treatment is always offered as a transdisciplinary team approach among neonatology who performs fiberoptic endoscopy, nursing, orthodontics, infant feeding, and oral maxillofacial surgery to position the pharyngeal component of the airway plate as precisely as possible. I thought the transdisciplinary approach concept was brilliant.

[Editor’s note: Tübingen’s studies include 2020, 2019, 2019, 2017, 2017, 2016, 2014, 2011, 2009, 2007, etc.]

So, early in 2020, I reached out to Dr. Christian Poets, the neonatology professor and medical director at Tübingen University Hospital. He appreciated my effort and interest in pursuing this transdisciplinary nonsurgical treatment approach for the first time in the United States. He said there were a few interested U.S. institutions in the past, but they never realized the treatment into fruition. He was willing to share clinical tips by email whenever I had questions. Since then, he and I became professionally trusting friends even though we never met before. That’s when I started to talk to my colleagues at Stanford who might be interested in working with me on this treatment concept. Naturally, there was some skepticism initially, because jaw distraction has been the standard of care and was working very well in avoiding tracheostomy. I continued presenting already published long-term clinical data to my colleagues in neonatology, plastics, genetics, nursing, infant feeding, pulmonology, and otolaryngology. That data had been published by centers that routinely use airway plates and many of them were from Tübingen University Hospital, one of the national Robin sequence centers in Germany. And one day, an RS baby showed up at the pediatric plastic surgery clinic with failure to thrive due to the small jaw. My plastic colleague asked me if I would treat the baby using this removable device and that is how I got to treat for our first Stanford RS baby using an OAP in our NICU. It would not have been possible to establish the OAP program here at Stanford without the significant support from the Division of Neonatology, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Division of Pediatric Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, our Hospital Administration (Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford), and multidisciplinary care experts in the NICU, nursing, otolaryngology, plastics, pulmonology, genetics, and infant feeding. If that’s Ok with you Philippe, I would like to take this interview opportunity to say special thanks to Drs. Jochen Profit (neonatology), Lawrence Prince (neonatology), Peter Lorenz (plastics), Rohit Khosla (plastics), Tulio Valdez (otolaryngology), Douglas Sidell (otolaryngology), Karthik Balakrishnan (otolaryngology), Rafael Pelayo (sleep medicine), and Shannon Sullivan (pulmonology and sleep medicine) at Stanford.

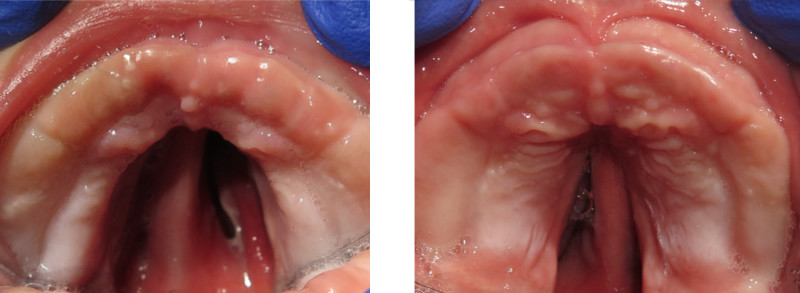

A palatal cleft is present in approximately 80-90% of babies with RS. Surgery to close the palatal cleft is usually performed when the baby is around 1 year old. In these two photos, taken before the OAP was worn (left) and after the OAP was worn for several months (right), we can see that the width of the cleft has substantially decreased; the RS baby’s cleft is beginning to close, naturally. This will make the palatal surgery easier to perform when the baby is 1 year old.

Q: What about your first RS patient? When you proposed the OAP treatment to your first RS mother and father, what did they say? Were they skeptical? And most importantly, how did the treatment go, I mean was the treatment successful?

A: I didn’t meet the father at first. A brave, non-English speaking mother brought her baby boy that day. He was one of natural triplets and he was the only one who was not growing well according to the mother. I explained the OAP treatment to her through the language translation service in the hospital and she was willing to give it a try. She asked me how many patients I have treated previously and I told her that her son will be my second patient for the airway management although I have extensive experience in treating neonates with facial oral deformities over 14 years. Mom seemed skeptical but trusted me enough to let me take care of her son. She was busy with her other two triplet babies at home and could not come to the hospital often. So, I checked on him day and night as much as possible.

The pandemic was getting really serious at that time and I remember I spent a lot time with him simply because visitors were not allowed except for the mother or father (only one parent at that time) and the NICU bedside nurses were not familiar with OAP handling and daily cleaning routines and bottle-feeding routines. So, I became almost a primary care giver for the baby during that time. The clinic and hospital were shutting down completely due to the pandemic and I had quite a bit of time to spend with him. He responded to the treatment very well. Obstructive breathing events decreased from over 69 events per hour before the treatment to 12 per hour (normal for this age) by the time he was discharged home. He was gaining weight nicely and taking the milk by the bottle close to 30% of the full feed. Total length of hospital stay was about 4 weeks. We published his treatment as part of a case series at the Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal early in 2021.

Q: What you just said about tongue position reminds me of when my own daughter was born. Her tongue was in that upright, vertical position, all the way in the back of her throat. When we tried to put the baby bottle in her mouth, the nipple actually pushed her tongue back even further, to the point where she’d start to gag and choke. Feeding was really, really difficult. It actually seems like many of the things we’re talking about here are connected. The OAP, by shifting the tongue forward, opens up the airway, which makes it easier for the baby to breathe; but it also corrects the position of the tongue, getting it into the flat horizontal position which is clearly better for feeding. I think that you and your colleagues at Stanford have described all of this as “disruptive therapy”. Could you explain what this means for someone like me, who doesn’t have a medical background?

A: The title “Disruptive Therapy Using a Nonsurgical Orthodontic Airway Plate for the Management of Neonatal Robin Sequence: 1-Year Follow-up” was an idea of my mentor and colleague Dr. Janice Lee, a renowned oral maxillofacial surgeon and Clinical Director at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) / National Institute of Dental Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) in Bethesda, Maryland, who appreciated the importance of the nonsurgical OAP treatment for the neonatal RS management in the surgery-dominant U.S. medical environment. Since the jaw distraction surgery (MDO) was first used on an RS neonate in 1998, MDO is currently the most prevalent and popular treatment option for RS babies in the United States, if not in the world. Even though the OAP was introduced with successful treatment outcomes much sooner than MDO, it has never been utilized at most parts of the world and none in the United Sates, which is puzzling.

“Disruptive therapy” in the title of the article has two meanings. One comes from the business theory by Clayton Christensen’s disruptive innovation, which is an innovation that quietly enters the existing market and eventually displaces established leading products. Our team at Stanford and NIH/NIDCR is now quietly introducing this innovative treatment approach to the United States with the belief that one day the OAP treatment will become the gold standard in the management of neonatal RS. The second meaning of “Disruptive therapy” is to describe the nature of the OAP treatment in correcting the tongue-based airway obstruction of RS babies. RS babies have truly abnormal tongue position and tongue behaviors that block the airway threatening the babies’ lives at any moment. Instead of leaving these disruptive tongue movements alone as the status quo, the OAP treatment counter-disrupts these disruptive tongue movements and actively train the tongue to behave as normally as possible for a few months, enabling the return of normal function and form of the mouth and face.

Pierre Robin Sequence and oral feeding with the orthodontic airway plate which is administered by Dr. HyeRan Choo, Clinical Assistant Professor of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, and her multidisciplinary team at Stanford. This successful feeding session was videotaped just two days after the baby received her orthodontic airway plate.

Q: In your paper, “Disruptive Therapy Using a Nonsurgical Orthodontic Airway Plate for the Management of Neonatal Robin Sequence: 1-Year Follow-up”, you went back to two of your OAP patients to see how they were coming along. You used computerized tomography, “CT” scans, to study the jaw bones of these RS babies. You said that based on the CT scans, the catch-up growth of the lower jaw, the mandible, was, and I think this was the word you used, “remarkable”. Can you please talk about this?

A: Yes, when we measured the dimensions of the mandible and compared the values with already published data of normal mandibles of one-year old babies, we found that the dimensions of the two OAP-treated babies’ mandibles were within the normative values of age matched healthy controls. The mandibles of the two RS babies prior to initiating the OAP treatment showed far smaller dimensions than those of the age matched healthy controls. We don’t have enough CT data that we can run formal statistical tests yet. However, our preliminary results from the radiographic comparison seem in agreement with the published data on the mandibular growth by the Tübingen University Hospital, although their data was based on clinical measurements on the face (soft tissue), rather than CT measurements (bone tissue).

This is an area where further research needs to be done with a bigger sample size. We speculate that the mandible’s growth is expedited for RS babies when the tongue is trained to stay forward and downward by the OAP treatment. The forward and downward positioning of the tongue also positions the mandible forward by muscular attachments. Subsequent to the forward jaw position, the tension inside the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) complex increases, which may give rise to expedited growth and remodeling of the TMJ complex that houses the growth center of the mandible and growth sites for jaw joint remodeling. Our speculation is derived from Melvin Moss’s functional matrix theory of “form follows function” in 1962. In other words, when we let RS babies breathe well by controlling the tongue (function), the mandible (form) will grow to sustain the corrected functions.

Q: If it’s OK I’d like to ask you about something which is not directly related to the OAP, but which has become a controversial subject for many RS parents and clinicians: prone/stomach sleeping. A study in the Lancet, one of the most respected medical journals in the world, indicated that prone sleeping increased the risk of SIDS, sudden infant death syndrome, by 13 times. Because of its known dangers, prone sleeping is condemned by healthcare providers throughout the entire world… except if the baby suffers from RS. In one of the papers you sent me before this interview, a study from the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, the authors wrote that “It is not our institutional practice to recommend prone positioning for neonates with RS… given the increased risk of sudden infant death.” So, the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital refuses to endorse prone sleeping. Does Stanford share the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital’s serious concerns about prone sleeping for RS babies? What is Stanford’s policy?

A: Thank you for pointing that out, Philippe.

Prone positioning is letting babies sleep on their tummy. It is one of the oldest management protocols for RS babies since the gravity will pull the jaw and the tongue toward the center of the gravity opening up the airway behind the tongue. However, as you mentioned, the Lancet study from 2004 showed that there is 13 times the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) when a baby sleeps in prone. In addition, a study from Paris in France in 2019 and the other from Los Angeles in the U.S. in 2020 showed that some RS babies breathe better in a supine position (on their back). Therefore, prone positioning should not be used as a default for any RS babies unless a sleep test confirms its therapeutic value. It is also very important to recognize that a prone positioning is not a safe long-term treatment solution for RS babies.

At Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, prone positioning is used as a temporary measure under the highest level of surveillance by trained medical professionals in the NICU until a definitive treatment such as MDO, tracheostomy, or OAP is conducted. Being able to sleep on their back comfortably is one of the most important criteria to meet before an RS baby is discharged from our hospital. From the moment the OAP is installed inside an RS baby’s mouth, we notice that the baby can breathe comfortably in a supine position because the tongue is stopped from prolapsing by the pharyngeal component of the OAP.

Q: I’ve got some last-minute practical questions for you. First a simple one: can we provide a link to your profile page on the Stanford website, so that RS families and clinicians can reach out to you?

Here are some helpful links:

- Dr. HyeRan Choo’s profile page on the Stanford University website

- Information about the OAP offered at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford

- An article written about Alianna, a baby girl born with Robin Sequence, who received the OAP treatment at Stanford

Q: Are you and your team at Stanford University’s Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital able to receive and treat RS babies coming from other US states?

A: Yes. In fact, we have already treated RS babies from a few different states outside California. All those treated with the OAP had no issues with breathing and bottle feeding on their own after a few months of OAP treatment. So, we completed the OAP treatment with confirmation for resolution of retrognathia/micrognathia (small jaw), glossoptosis (prolapsing tongue), and upper airway obstruction (breathing difficulty) using flexible endoscopy, polysomnography, and clinical morphologic evaluation of the jaw. The babies no longer needed jaw distraction surgery or tracheostomy afterwards.

Q: Are you collaborating with other American hospitals to share the skills and techniques which you and your team have developed at Stanford? If not, would you be open to such exchanges with other US hospitals?

A: Yes, after I presented the Stanford protocol for the management of neonatal Robin sequence at the most recent International Robin Sequence Consensus Meeting in Tübingen Germany in 2022, we received multiple inquiries from other hospitals with interest in launching their own OAP program not only in the North America and also in Europe. We are thrilled with the opportunities to share our experience with them and help them initiate their OAP programs.

Dr. Choo I’d like to say something now not on behalf of the organization I’m with, but just on behalf of myself as an RS parent. In America, RS care has been largely dominated by surgery; in many instances surgery seems to simply be taken for granted. You and your colleagues at Stanford decided to adopt a ground-breaking non-surgical approach. I think you’ve shown a tremendous amount of open mindedness and courage to pursue this path – a less invasive way to treat our RS babies. As an RS parent I sincerely thank you, not only for sharing your time with us for this interview, but also for the amazing work you’re doing to help RS babies. Thank you.