Pierre Robin Sequence – Information Document for Parents

> Lire la version française ici

> Lees hier de Nederlandse versie

Dear Fellow Parents,

Although Pierre Robin Sequence is described in Europe’s Orphanet Rare Disease Database, and in America’s NORD Rare Disease Database, and in the GARD Genetic and Rare Diseases Database, the information provided in these databases seems to be written for physicians, and not for parents. Our goal was to produce the kind of document each of us wishes we as parents could have had, when the doctors first told us that our baby had Pierre Robin Sequence.

To create the document we collaborated with healthcare providers – doctors, nurses, surgeons and orthodontists – and also parents and Pierre Robin Sequence patient groups. The document went through many drafts but we’re now sharing it with others. The current version provides information about Pierre Robin Sequence, and various treatments, both surgical and non-surgical. Since the document is for parents like us, without a medical background, we used plain language and clear explanations. And thanks to the continuous and ongoing involvement of all the different healthcare providers, the document has been confirmed as being medically accurate and objective. We know there’s always room for improvement and we will definitely keep trying to make it better, so we welcome all feedback, both positive and negative, on the Contact Page.

We send each of you fellow Pierre Robin parents out there our very best wishes and encouragement.

Kind regards,

Philippe Pakter

Pierre Robin Europe Foundation (Stichting Pierre Robin Europe)

Pierre Robin Sequence

The Condition, and Various Treatments

Pierre Robin Sequence Information Document for Parents

Introduction to Pierre Robin Sequence

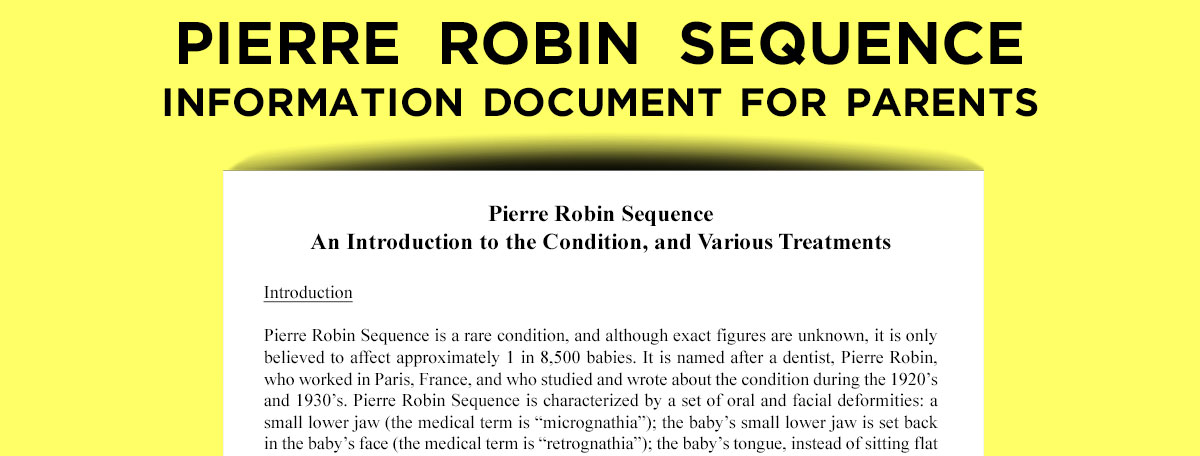

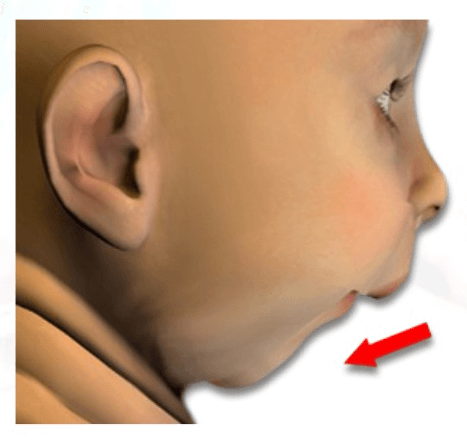

Pierre Robin Sequence is a rare condition, and although exact figures are unknown, it is only believed to affect approximately 1 in 8,500 babies. It is named after a dentist, Pierre Robin, who worked in Paris, France, and who studied and wrote about the condition during the 1920’s and 1930’s. Pierre Robin Sequence is characterized by a set of oral and facial deformities: a small lower jaw (the medical term is “micrognathia”); the baby’s small lower jaw is set back in the baby’s face (the medical term is “retrognathia”); the baby’s tongue, instead of sitting flat in the mouth, sits up, in the back of the throat, in an angled or vertical position (the medical term is “glossoptosis”); and in most cases, the baby has a cleft palate, not outside, but inside of the baby’s mouth. The problems these babies face include upper airway obstruction, breathing difficulties, and feeding difficulties. The severity of these difficulties varies from baby to baby.

Micrognathia – the medical term for a small lower jaw.

The baby’s tongue, instead of sitting flat in the mouth, sits up, in the back of the throat, in an angled or vertical position; the medical term is “glossoptosis”.

Pierre Robin Sequence actually goes by several slightly different names. Some healthcare providers refer to it as Pierre Robin Sequence; others call it Pierre Robin Syndrome, or Robin Sequence, Robin Anomalad, RS, PRS, etc. In this document, we will use the simple and abbreviated name, “Robin Sequence”.

While Robin Sequence falls under the broad category of rare diseases, and is included in the major European and American rare disease databases (Orphanet, NORD, and GARD), it can also be described as a condition, and as a sequence. But why is Robin Sequence described as a “sequence”? The reason is that with Robin Sequence, one problem leads to another problem, in a chain of events – in a “sequence”. For example: during the normal development of a baby inside of the mother’s womb, babies begin the growth process with a divided, open palate; the roof of the baby’s mouth is open. At around 8 to 12 weeks into the pregnancy, the two sides of the baby’s palate normally join together, and close. However, in babies with Robin Sequence, the baby’s lower jaw is very small. Because the lower jaw is very small, there is almost no space for the baby’s tongue; the baby’s tongue can’t lay down flat in a flat, horizontal position, inside of the baby’s mouth. Instead, the baby’s tongue gets bunched up, and pushed to the back of the baby’s mouth, in an angled, upright, vertical position. The problem is that if the baby’s tongue is in this vertical position, then the baby’s palate can’t join together and close – because the tongue is in the way. Thus, the small lower jaw leads to a sequence of events: with a small lower jaw, the tongue doesn’t have enough space; therefore it’s pushed up, in a vertical position; this in turn prevents the palate from closing, because the tongue is in the way. The result is a small cleft, a hole, in the roof of the baby’s mouth, the palate.

It is important to note that not all babies with Robin Sequence have a cleft palate. Some just suffer from the very small lower jaw (“micrognathia”), which is deeply set back and receded (“retrognathia”), and a tongue which is in the raised, vertical position, in the rear of the baby’s throat (“glossoptosis”). Since not all Robin Sequence babies have a cleft palate, recent efforts have been made to focus not on the presence or absence of a cleft palate; instead, doctors are focusing more on whether the baby is showing signs of upper airway obstruction, which can create very serious risks to the baby’s life and long-term health. At a May 2017 meeting in Toronto Canada, doctors from all over the world who treat Robin Sequence and who study Robin Sequence got together to discuss the way forward. The doctors reached a general agreement, a consensus – the three characteristics which are necessary for a diagnosis of Robin Sequence are micrognathia, glossoptosis, and upper airway obstruction; a cleft palate is not required for a diagnosis of Robin Sequence.

Robin Sequence often appears together with other medical conditions. According to Orphanet, Europe’s database of rare diseases, approximately half of the babies who are born with Robin Sequence are also born with another condition. The other condition could be Stickler Syndrome, or Treacher-Collins Syndrome, or any of a number of other rare conditions. These are serious conditions all by themselves; each one presents its own symptoms and problems. Thus, babies suffering from Robin Sequence show a great deal of variation in terms of exactly which symptoms each baby has. Since associated conditions can create so many additional medical risks, it is critical for the doctors treating your baby to take a hands on, active approach. Your baby’s breathing problems are probably taking center stage, because breathing problems are of immediate, grave concern – babies, like all humans, need air – but your doctors should also look for associated conditions, carry out genetic testing, and perform neurological examinations, at the same time that they are dealing with your baby’s breathing difficulties.

In addition to breathing difficulties, babies suffering from Robin Sequence may also face feeding difficulties. A cleft palate, if present, can aggravate the baby’s feeding difficulties, since a cleft makes it difficult for your baby to create a suction effect inside of his or her mouth. Also, the extra effort your baby needs for breathing can itself be exhausting, leaving him or her less energy and enthusiasm to feed.

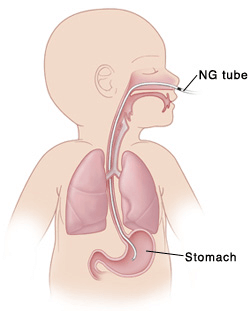

Feeding difficulties can interfere with weight gain and normal growth (the medical term is “failure to thrive”). These feeding difficulties can be serious, and may require the use of a nasogastric tube – a tube which enters the baby’s nose and goes all the way down into the baby’s stomach, to deliver milk, and ensure that the baby receives adequate nutrition. If feeding difficulties continue, the baby may undergo surgery and receive a gastrostomy tube – a feeding tube which enters the baby’s body through the tummy, and goes directly into the baby’s stomach.

Most children with a cleft palate suffer from a build-up of fluid behind the eardrum. Normally, the muscles in the palate make sure that fluid is drained from the middle ear, to the throat. However, in a baby with a cleft palate, the muscles in the palate are not in their normal, natural position; this makes it difficult or impossible for these muscles to do their job, and drain the fluid. This can lead to a build-up of fluid behind the eardrum. If this fluid build-up behind the eardrum causes hearing problems, it may be necessary to surgically insert a tiny tube into each eardrum. These tiny tubes help provide ventilation, air flow between the inside of the ear and the outside world, which reduces fluid build-up. Babies with Robin Sequence may also suffer from ear infections. Ear infections can cause temporary hearing loss, which can lead to problems with speech and language development.

If your baby does have a cleft palate, then the cleft will have to be closed with surgery. This is often done when the baby is approximately 1 year old, depending on various factors, including the child’s weight – does the baby have enough weight and strength to endure surgery – and whether your baby still has breathing difficulties at that time. Children with a cleft palate have a higher risk of delayed or defective speech development; your baby may in the future need assistance from speech therapists.

Treatments for Robin Sequence

Feeding Difficulties

When a baby with Robin Sequence faces difficulties feeding, it can place a tremendous burden on you, the parents. You may try every single baby bottle available on the market, and spend an hour or more trying to feed your baby every single meal, four or five times a day – and still find it difficult or even impossible to provide your baby with the milk he or she needs. Making things even harder, vomiting can be a common occurrence – sometimes daily, sometimes several times a day. Babies with Robin Sequence also face an increased risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease, or “GERD”. GERD is a condition in which the contents of your baby’s stomach – not only the milk, but also your baby’s natural stomach acids – flow up into the esophagus, the tube which runs between your baby’s stomach and mouth. This stomach acid can irritate your baby’s esophagus and cause your baby a great deal of discomfort and pain. For you as a parent, all of this this can be both physically challenging and emotionally depressing. Patience, and the faith that things will gradually improve, are critical.

If your baby is unable to consume a sufficient volume of milk, you may be able to add nutritional supplements to the milk – for instance, Duocal, a special powder which is rich in protein and fats. Another possibility is to feed your baby a specially formulated, highly enriched milk substitute. The names of these products will be different from country to country, but one example is Infatrini. This medical product comes in a liquid form, and is particularly rich in the type of nutrition which a growing baby needs. Do not wait until your baby loses a lot of weight before taking action. If your baby is suffering from feeding difficulties, maintain close and ongoing contact with the nursing staff and doctors; tell them about your difficulties, and ask them for help.

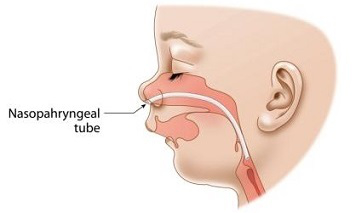

If feeding difficulties make it difficult or impossible for the baby to drink enough milk, then the baby may receive a nasogastric tube, which enters the baby’s nose, and descends down into the baby’s stomach.

If feeding difficulties make it difficult or impossible for the baby to drink enough milk, then the baby may receive a nasogastric tube, which enters the baby’s nose, and descends down into the baby’s stomach.

For long term feeding difficulties, the baby may undergo surgery and receive a gastrostomy tube, which enters the baby’s body through the tummy, and goes into the baby’s stomach.

For oral feeding, special bottles and techniques may be required; specialised assistance is strongly advised, because the feeding difficulties of a baby with Robin Sequence can be highly challenging, even for the experts.

Playtex

The Playtex Nurser bottle has an internal plastic liner or bag. This internal plastic bag can be gently pressed with your fingers when you are feeding your baby, which causes the milk to gently flow.

The small plastic bag drops into the bottle, from the top. On the bottom, the Playtex bottle is actually open, which means you can insert your fingers into the bottle.

By gently pressing on the flexible plastic bag inside of the Playtex nurser bottle, the milk will slowly flow into your baby’s mouth.

Medela

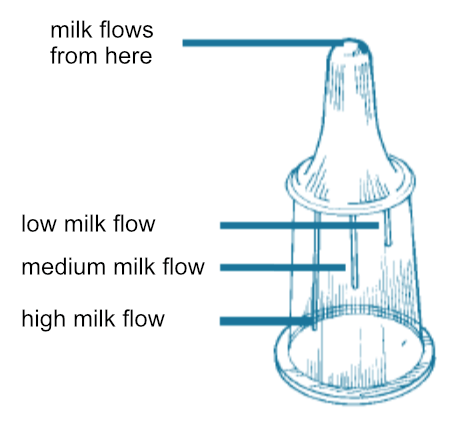

The Medela bottle – a bottle which is specially designed for babies with feeding difficulties. Applying gentle pressure just next to the yellow ring will cause the milk to slowly flow.

Medela bottle – the nipple. The flow of the milk through the Medela bottle’s nipple can be adjusted by aligning the baby’s nose with one of the three lines on the base of the nipple; each line on the nipple produces a different flow rate. Slow flow: the short line. Medium flow: the middle line. High flow: the long line.

Dr. Brown’s

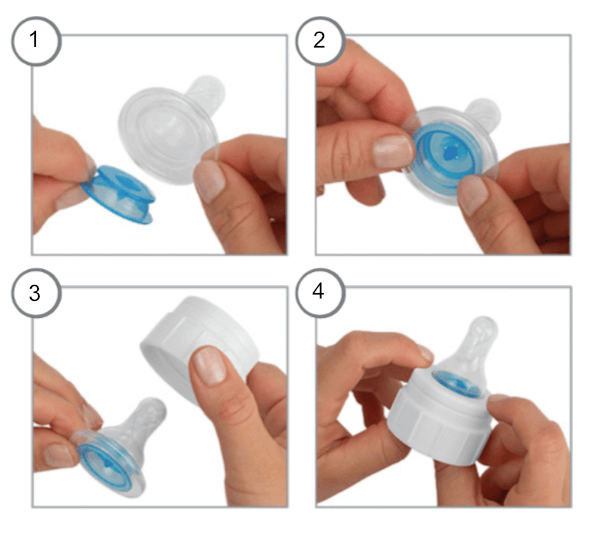

The “Specialty Feeding System”, produced by a company called “Dr. Brown’s”, looks like a regular baby bottle. In fact, it works differently…

The Dr. Brown’s “Specialty Feeding System” uses an “Infant Paced Feeding Valve”, a small, blue plastic disk which fits inside of the base of the nipple. The manufacturer, “Dr. Brown’s”, describes this as a compression based system. Essentially, the baby gets the milk to flow from the nipple by applying compression – by gently chewing on the nipple – rather than by suction (suction can be difficult for babies with Pierre Robin Sequence and cleft palate). Important note: Dr. Brown’s sells many different types of baby bottles. If you are interested in this “Specialty Feeding System”, make sure that you are ordering the Dr. Brown’s Specialty Feeding System with the blue valve (the “Infant Paced Feeding Valve”) and the blue insert.

Breathing Difficulties

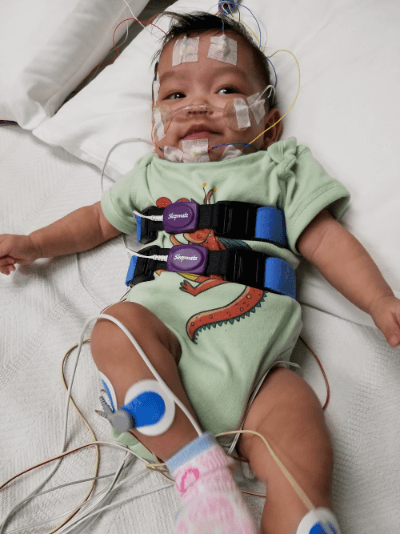

When it comes to Robin Sequence breathing difficulties, different doctors favor different treatment strategies. However, no matter which treatment or treatments your local healthcare provider prefers, the first step is to determine how severe your baby’s breathing difficulties are. At this time, the most objective and scientific way to measure the severity of your baby’s breathing difficulties is through a test called a “polysomnography”, a “PSG”. A PSG is often referred to as a “sleep study”, because this test is carried out while your baby sleeps. To carry out a PSG/sleep study, your baby will be connected to various sensors right before he or she goes to sleep. Then, all through the night, while your baby sleeps, the sensors will monitor and record your baby’s breathing patterns, chest movements, oxygen levels, and other vital signs.

A baby who is about to undergo a sleep study. The sleep study is a painless test – and it is a very important and fundamental procedure for Robin Sequence babies to undergo.

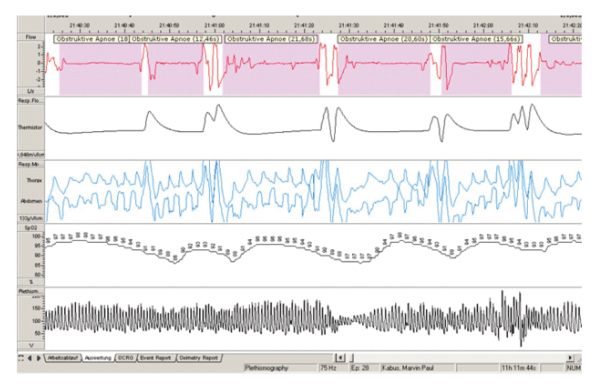

The data which your baby’s PSG/sleep study produces will help show whether your baby’s breathing is mildly obstructed, moderately obstructed, or severely obstructed. Doctors do not yet agree on exactly what level of breathing obstruction qualifies as mild, or moderate, or severe, but in any case, the information produced by the PSG/sleep study serves as a guide, helping doctors to determine which treatments might be appropriate. This type of approach is called “evidence-based decision making”. What this means is that the healthcare decisions which you and your physicians make about your baby are based on objective, scientific data – the results of the PSG/sleep study – rather than on this person’s feeling, or that person’s opinion. Evidence-based decision making is strongly favored in medicine today, so in treating Robin Sequence, the PSG/sleep study plays a fundamental role.

The results of a sleep study. This data provides medical evidence of the Robin Sequence baby’s breathing difficulties, allowing both you and the physicians to see whether your baby’s breathing problems are mild, moderate, or severe. For treating Robin Sequence babies, the sleep study is absolutely fundamental; this is called “evidence-based medicine”.

A baby suffering from Robin Sequence should undergo a PSG/sleep study before undergoing treatment for breathing difficulties, and after the treatment as well, to see whether the treatment relieved that baby’s breathing difficulties, and if so, by how much. Since the PSG/sleep study is currently the most objective and scientific way of measuring the severity of your baby’s breathing difficulties, it is not just used in the treatment of individual babies. This same tool, the PSG/sleep study, is also used when doctors carry out medical studies to scientifically evaluate the effectiveness of a particular Robin Sequence treatment. The PSG/sleep study is a standard Robin Sequence tool, and it is a very important test which your baby should undergo. If your local hospital is unable to carry out a PSG/sleep study, ask your doctor whether the test can be carried out at another hospital nearby.

To deal with the breathing difficulties of babies suffering from Robin Sequence, a number of different treatments have been used, depending on how serious the baby’s breathing difficulties are. Which treatment you choose for your baby is a critical decision which you should think about very carefully, and also discuss with your healthcare provider. Robin Sequence is rare, and when it comes to a rare disease or complex condition, expert help may be difficult to find. If your local healthcare provider does not have specialised knowledge of Robin Sequence, it is very important that you look for and find specialists who are familiar with it, and who do have experience treating it.

While prone (stomach) position was used for many years as a default way of trying to relieve the baby’s upper airway obstruction and breathing difficulties, other methods have been developed. In actual practice, the doctors in your local hospital will most likely propose the treatment which they happen to be familiar with – because they received training in that particular technique. However, if you reach out to other parents, on RareConnect, or in a Facebook group focusing on Robin Sequence, you might discover that the doctors in a different hospital, in your same exact country, propose a different treatment – because that is the treatment which they happen to know, and which they use in that hospital. It is a good idea to use the internet and reach out to other families, and other experts, to learn about the various treatments which might be available for your baby. This way you can learn about the experience which other parents like you had, with each of these different treatments.

Some of the treatment methods described below date back many years, and are being reviewed by medical professionals to find more effective and less invasive techniques. Not all doctors and not all parents agree on the best ways to treat Robin Sequence, but almost everyone agrees on one general principle: whenever possible, nonsurgical treatments should be tried first, in order to avoid performing surgical operations on these small babies. Generally speaking, non-surgical techniques require months of devoted treatment, which does put a certain burden on you, the parents. However, those who support these non-surgical treatments point out that it allowed their baby to avoid invasive surgery. As a general trend, hospitals first try to treat a baby without using surgery, and reserve surgery for those babies where the non-surgical options could not be used, or failed.

Prone Positioning (placing the baby on their stomach)

A baby suffering from Robin Sequence tends to have the greatest difficulties breathing when the baby is placed on his or her back. This is because when the baby is laying on his or her back, the baby’s tongue, which is already in a raised position, blocking the entrance to the throat, can fall back even further, and seriously obstruct the baby’s airway. For this reason, babies suffering from Robin Sequence are often placed to sleep on their stomach, in the “prone” (stomach) position, or on their side. The practice of placing Robin Sequence babies to sleep on their stomach was first proposed by Pierre Robin himself, in 1934, over 80 years ago.

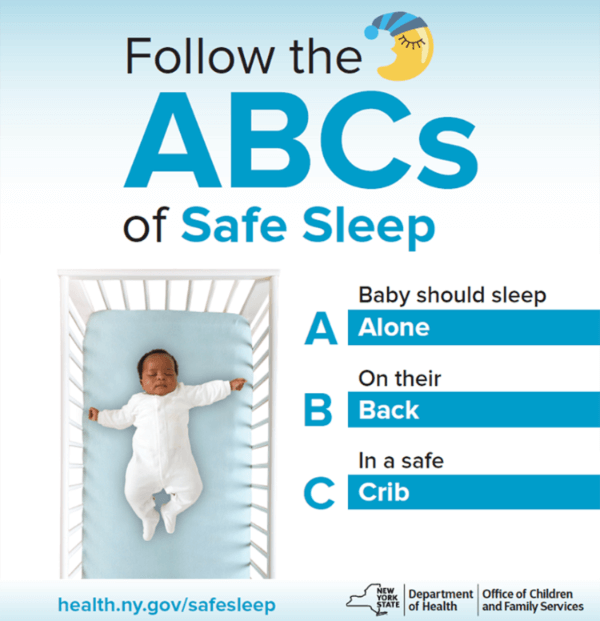

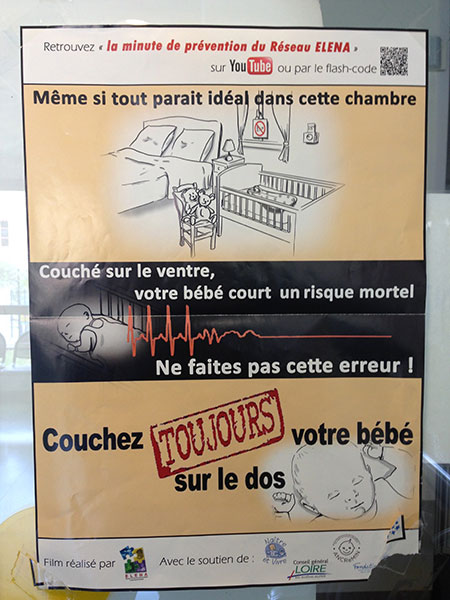

The prone sleeping position – placing the baby to sleep on her stomach. This practice has become highly controversial, because medical studies have consistently found that prone (stomach) sleeping substantially increases the risk of SIDS (Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, also known as “Crib Death”).

A poster in America, urging parents to only let babies sleep on their back.

A poster in France, with a strong warning about prone (stomach) sleeping: “Even if everything in this room looks perfect… a baby sleeping on her stomach runs a mortal risk. Do not make this mistake! Your baby should ALWAYS sleep on her back.”

Based on what we have learned over the last 80 years concerning the serious risks of placing babies to sleep on their stomach, this practice of prone (stomach) positioning for babies suffering from Robin Sequence has become highly controversial. It offers a possible improvement, but it is not ideal. Prone (stomach) positioning should only be done when your baby is connected to a machine which monitors your baby’s pulse and oxygen level.

OTHER OPTIONS WITHOUT AN OPERATION:

Nasopharyngeal Airway (also called “NPA tubes”)

In order to maintain an open channel between your baby’s nose and your baby’s upper throat (the medical term is “nasopharynx”), doctors may insert a flexible tube into and through one of your baby’s nostrils. This soft flexible tube is called a nasopharyngeal airway; it ends just above the baby’s “epiglottis”. The “epiglottis” is the medical term for the small flap inside of the throat, which acts like a lid on the top of the baby’s windpipe. The nasopharyngeal airway, also called the “NPA” tube, helps to relieve the Robin Sequence baby’s upper airway obstruction, by keeping the baby’s tongue from falling back, and blocking the top of the baby’s throat. The NPA tube is a widely used treatment for babies suffering from Robin Sequence in the United Kingdom. Most parents say that their baby tolerated it well, and that they were happy that it allowed their baby to avoid surgery. If the NPA tube gets filled with mucous, or milk, a portable suction machine can be used to clear the tube. Parents also learn how to change the NPA tube themselves, and insert a new tube – a process which can be difficult and scary for parents in the beginning, but which becomes much less difficult with experience and practice. Depending on the baby’s breathing difficulties, the baby may use the NPA tube for anywhere from 3 months to 6 months to 9 months, or some period of time in between.

The NPA tube is a flexible tube which enters the nose and ends just above the baby’s “epiglottis”, the small flap inside of the throat which acts like a lid on the top of the baby’s windpipe. The purpose of the NPA is to maintain an open channel between your baby’s nose and your baby’s upper throat

Breathing machines (including “CPAP”)

A Robin Sequence baby suffering from moderate to severe breathing difficulties can be attached by tubes to a breathing machine, in order to receive manual breathing assistance. The umbrella term for ventilation assistance using breathing machines is “noninvasive respiratory support” – “non-invasive”, because surgery is not required in order to provide this breathing assistance. One form of non-invasive respiratory support, Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (“CPAP”), involves the application of a flow of air, at a specific pressure and rate, into the baby’s airway. The air is literally pushed from the machine, into a set of tubes, through a mask which is attached to the baby’s face, and into the baby’s lungs.

A Robin Sequence baby receiving respiratory support with Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (“CPAP”).

Generally speaking, CPAP requires long-term hospitalisation. Long-term hospitalisation prevents the newborn baby from going home to his or her parents, comes at a high financial cost, and exposes the baby to the risk of hospital borne illnesses. Ventilation assistance also requires the baby to be attached for long periods of time each day to an external breathing machine, which substantially reduces mobility, for both the baby, and the parents.

A Robin Sequence baby receiving respiratory support in the ICU.

In countries such as Australia, where vast distances may separate patients and their hospitals, babies are often hospitalised at home. With home hospitalisation, the hospital’s ventilation machines are transported to and installed inside of the parents’ home. The CPAP is then administered to the baby by the parents, who are trained how to operate the breathing machine and equipment. In the beginning, the baby must be connected to the breathing machine 24 hours a day. When your baby’s breathing improves, this can be reduced, so that your baby only needs to be connected to the breathing machine when he or she sleeps.

The aim of CPAP’s breathing machines is to avoid invasive surgery, including tracheostomy, which will be described below; almost every doctor agrees that nonsurgical treatments should be tried first, in order to avoid performing surgical operations on these small babies.

Tübingen Palatal Plate (also called the “TPP”)

A “palatal plate” is a small device made of plastic or other durable material which is worn inside of the mouth, on the palate, or roof of the mouth. Robin Sequence experts in Tübingen, Germany have developed a specially modified version of the palatal plate, for babies suffering from Robin Sequence: the Tübingen Palatal Plate (the “TPP”). The TPP is a small oral device worn inside of the baby’s mouth; it resembles the oral retainers which children wear after their teeth-straightening dental braces have been removed. The TPP is not surgically attached – instead it sticks to the baby’s palate with denture adhesive, and two adhesive strips. Like dentures, the TPP can be inserted or removed by the parents whenever they want, without requiring doctors or nurses. The difference between the TPP device and other palatal plates is that the TPP has a small extension in the rear, an extension whose shape, angle and length are precisely designed and manufactured for each baby by a multidisciplinary German team. The purpose of this extension is to push the baby’s tongue down, in a flat, horizontal position, out of the way of the baby’s throat. By actively pushing your baby’s tongue down into its normal and natural position, the TPP unblocks the throat, eliminates your baby’s breathing difficulties, and allows your baby to sleep safely and silently, even on his or her back – without any tubes, machines, or other equipment.

Above, a Tübingen Palatal Plate.

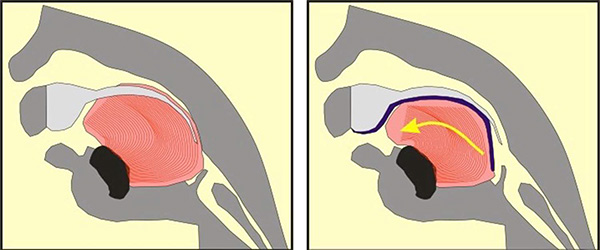

An illustration of how the Tübingen Palatal Plate (TPP) works. The large pink/red object is the baby’s tongue. In the cross-section image on the left, the Pierre Robin Sequence patient has no TPP device; the abnormal rear position of the tongue blocks the upper airway, creating potentially life-threatening breathing and eating difficulties. In the illustration on the right, the TPP device is in place; it is represented by a dark blue line. The dark blue line begins at the upper alveolar ridges (where the upper front teeth will eventually grow), continues along the upper palate, covers the cleft in the palate, and then extends down. In the image on the right, toward the right side, we can see this downward dipping dark blue line extension pushing the base of the tongue left, toward the front of the mouth. By shifting the tongue forward, the TPP device instantly liberates the throat – without surgery.

The TPP is removed by the parents once a day for cleaning, using a toothbrush, the way one would clean a set of dentures. After the first 2 months of wearing the TPP, the baby has to return to the hospital for an examination of the baby’s breathing – a “polysomnography”, also called a sleep study. The sleep study is done in order to confirm that the baby’s breathing is still unobstructed and free. If necessary, the TPP will be slightly modified, to account for the natural growth of the baby’s mouth. Altogether, the TPP is worn for a period of between 3 to 5 months. After this period is over the lower jaw has grown forward, so the tongue has enough space to lay down horizontally and flat, and not cause breathing problems any more. The baby no longer needs to wear the TPP in his or her mouth; the therapy is complete.

OPTIONS WITH AN OPERATION:

Tongue-Lip Adhesion (also called “Labioglossopexy”)

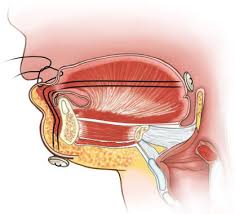

Another Robin Sequence treatment, first proposed over 100 years ago, is the practice of removing the baby’s upper airway obstruction by literally sewing the baby’s tongue down, onto the baby’s lower lip. The goal is to force the tongue to remain in a horizontal position, down and out of the way of the baby’s airway and throat.

Tongue-Lip Adhesion (also called “Labioglossopexy”).

Tongue-Lip Adhesion involves sewing the baby’s tongue down, onto the baby’s lower lip. The goal is to force the tongue to remain in a horizontal position, down and out of the way of the baby’s airway and throat.

Tongue-lip adhesion, also called labioglossopexy, has mixed results in relieving breathing problems; in some hospitals the success rate has been approximately 70%, while in other hospitals the success rate has been lower. Babies can experience complications from this operation; “dehiscence” is when the stitches accidentally come out of the baby’s tongue, several weeks or several months after the initial surgery; the surgeon then has to sew the baby’s tongue back down again. All babies undergoing tongue-lip adhesion eventually have to have a final surgery, in order to remove the stitches, and release the tongue from the lip. Tongue-lip adhesion is less invasive than other surgical techniques, but when tongue-lip adhesion fails, the next step, generally speaking, is for the surgeon to carry out a more invasive surgical treatment – mandibular distraction osteogenesis, which is also called “jaw distraction”.

Mandibular Distraction Osteogenesis (also called “Jaw Distraction”)

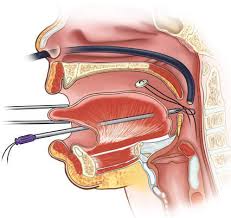

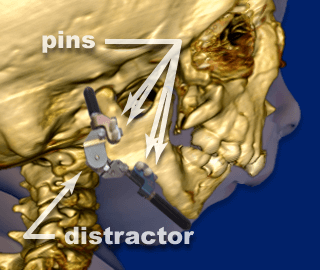

Another surgical option to relieve the Robin Sequence baby’s upper airway obstruction is to physically lengthen the baby’s undersized lower jaw using a procedure called “Mandibular Distraction Osteogenesis”. Mandibular Distraction Osteogenesis is also referred to as “Jaw Distraction”. While the baby is under general anesthesia, a surgeon cuts through the bones in the baby’s undersized, lower jaw, the mandible. The surgeon then installs a device called a distractor, which uses special screws called “pins.” In the week or two following the initial surgery, the screws on the distractor are turned, approximately 1 to 2 millimeters per day. This creates tension, and moves the bones of the baby’s mandible apart. New bone then grows (“osteogenesis”) and fills in the gaps created by the distractor. While the new bone is growing, the baby continues wearing the distractor device at all times.

Mandibular Distraction Osteogenesis. The surgeon installs a device called a distractor, which uses special screws called “pins.”

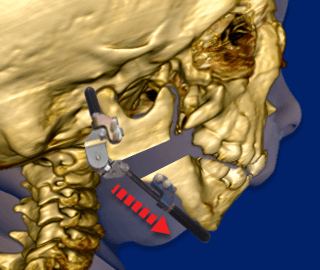

Following the initial surgery, the screws on the distractor are turned, approximately 1 to 2 millimeters per day. This creates tension, and moves the bones of the baby’s lower jaw (“mandible”) apart.

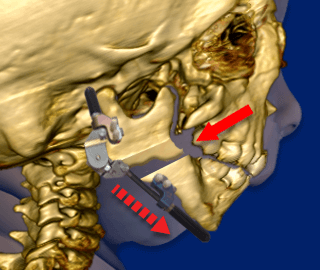

New bone then grows (“osteogenesis”) and fills in the gaps created by the distractor. While the new bone is growing, the baby continues wearing the distractor device at all times.

Surgeons performing Mandibular Distraction Osteogenesis / Jaw Distraction emphasize its proven ability to relieve upper airway obstruction by physically increasing the length of the lower jaw, giving the tongue more space to lay down in a flat, horizontal position. Mandibular Distraction Osteogenesis is an invasive surgical procedure, and complications can occur: infections where the pins enter the bones, scarring on the baby’s face, tooth damage, facial nerve damage, and device failure.

Tracheostomy

A tracheostomy is a surgical procedure which involves the creation of a surgical incision in the baby’s throat, in order to place a tube directly into the baby’s windpipe. The tube is inserted through the incision, just below the baby’s vocal cords. The tube allows air to enter the baby’s lungs and bypass the baby’s upper airway, which remains obstructed. According to one surgeon, “Unfortunately, several morbidities have been associated with tracheostomy, including increased risk for tracheomalacia, chronic pneumonia, laryngeal stenosis, intellectual and physical impairments, compromised social interactions, and a requirement for complex nursing care and parental education. In addition, the long-term benefit of tracheostomy is questionable, as tracheostomy is associated with increased cost of medical care due to frequent emergency room visits for treatment of pneumonia.” The tendency today is to reserve tracheostomy for critical situations where other treatments could not be used, or did not work.

A baby with a tracheostomy.

A Multidisciplinary Team of Experts

Robin Sequence is a complicated medical condition which can have effects on different parts of your baby’s body. Often, the baby’s breathing is affected, and these breathing difficulties can be dangerous. Babies with Robin Sequence also tend to have problems with sucking, swallowing, and feeding. But in addition to this, your baby could potentially suffer from central nervous system issues, neurologic abnormalities, or other medical conditions. For you, the parent of a newborn baby, this may sound terrifying – but the point is not to scare you. The point is to emphasize how important it is to find a real multidisciplinary team of highly specialised doctors who have experience dealing with this particular medical condition, Robin Sequence – and to make sure that the multidisciplinary team acts now, not later, in order to ensure the health and to promote the proper development of your newborn child.

Early intervention by a multidisciplinary team of experts, in close and ongoing collaboration with you and your family, is absolutely critical. A baby with a simple case of cleft palate, and a baby with cleft palate and Robin Sequence, a rare and complex disease, have very different medical needs. The proper treatment of Robin Sequence requires more than just a general pediatrician and a surgeon. The team treating your baby should also include specialists from neonatology (doctors who specialize in treating newborn babies with problems or illnesses of some kind), genetics (to test whether your baby may be suffering from an associated genetic condition), a pediatric sleep specialist (who will use special equipment to study your baby’s breathing and oxygen levels during a full night of sleep), an ophthalmologist (who will study your baby’s eyes, and check for signs of Stickler’s Syndrome), a speech therapist (who doesn’t just help with speech, but also with feeding problems), a developmental pediatrician (who will monitor your baby’s physical and intellectual development), an otolaryngologist (an ear/nose/throat specialist, who will watch for problems with your baby’s ears, and hearing), an orthodontist (who may need to carry out dental work, or create an oral palatal plate)… this is the type of team which a baby with Robin Sequence needs in order to have the best possible chance in life.

As part of your baby’s multidisciplinary team of experts, experienced nurses will be absolutely critical; they are among your most important allies. Whether your baby is in the intensive care unit, or at home, with you, the nurses caring for your baby are like the soldiers on the front line. Nurses will be the ones who struggle to help you manage your baby’s Robin Sequence feeding difficulties, who closely monitor your baby’s weight and growth, who train you, the mother and the father, how to care for your baby on a day-to-day basis, who will give you precious tips and advice based on years of experience caring for countless children… and they will be the bridge connecting you with the various specialists in the multidisciplinary team.

One of the hardest things about having a baby with Robin Sequence is that since the condition is rare, expertise about the condition is difficult to find. Treating a baby with Robin Sequence requires a special concentration of expertise, and your local healthcare center may not have the special concentration of expertise which your baby needs. If your local healthcare provider’s experience with Robin Sequence is limited, then it would be a good idea for you or your local doctor to make contact with one of your country’s centres of expertise for this rare condition. In the European Union, you can visit the Orphanet website, at Orpha.net, look up Pierre Robin Sequence, and scroll through the results to find a centre of expertise located near you.

Conclusion

Preferences, familiarity and availability of treatment methods can vary widely from country to country and region to region. As mentioned earlier, you can use RareConnect, as well as Facebook’s Robin Sequence support groups, to reach out to other families. You can ask them, honestly and directly, what they think of various treatments, based on the actual experiences they had. Many, many parents out there have gone through exactly what you are going through right now. You will be surprised and encouraged to find out how eager they are to share information with you, and support you, during this confusing, painful and often overwhelming time. Do not lose hope. Reach out, and connect with other parents. It will really give you a lot of relief when you see that you are not alone.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This document was produced as part of a joint collaborative effort involving a number of doctors, nurses, surgeons and orthodontists, including Corstiaan Breugem, Peter A. Mossey, Sirpa Railavo, Pia Vuola, Ulla Elfving-Little, Elina Swan, Janne Suominen, as well as parents, Robin Sequence patient groups, and Facebook groups, in the European Union and beyond. Thank you to each and every one of you who helped. If you would like to provide feedback on this document, or about your own experience with Robin Sequence, please send a message to Stichting Pierre Robin Europe (the Pierre Robin Europe Foundation) on the Contact Page.